More than two decades have passed since the collapse of the Soviet Union. In a supposedly conformist Soviet society there were many critically-thinking people who formed underground groups. Their goal was demanding state compliance with human rights laws that were guaranteed to them by the Soviet constitution; however, these guarantees were not enforced by the Soviet government. As a result of their protests, dissidents incurred harassment, persecution, imprisonment, or death by the KGB; simultaneously, their families were also oppressed by the state. The concentration camps and political jails, which were frequently referred to as ‘Universities,’ became centers of intellectual activity that provided intelligent dissidents from across the USSR with opportunities to meet and exchange ideas with each other. In addition, uncensored Soviet history, such as the crimes of the regime, was concealed in these locations from the rest of society with the imprisonment of any witnesses to this criminal activity. Non-imprisoned intellectual thinkers learned information about these so-called ‘white spots of history’ as prisoners and their families disseminated it. A great deal of this secret information has currently become public, though living witnesses are still a valuable source. As the United States hosted a number of Soviet dissidents, we have a great opportunity to meet them in person and record their stories. We expect to encounter facts that are not known yet widely. It allows us to study their private stories in the context of the Soviet dissident movement and history.

The goal of the project ‘Soviet Dissidents’ is the collection and video recording of the stories of Soviet dissidents and their family members, who are currently U.S. citizens, and making the material available to large audiences in Russia and the United States. The interviews focus on the daily lives of political prisoners, human rights activists, and their families in circumstances that involve KGB oppression and harassment.

OBJECTIVES

- Finding out details of daily life inside of the closed circle of

Soviet dissidents and human rights activists.

- Detecting earlier unknown facts.

- Revelation of reasons for their resistance to the Soviet regime.

- Detecting influence of the dissident lifestyle on family

members’ lives.

- Understanding the reasons for the critical thinking formation and

overcoming of fear by the minority of the Soviet society.

- Defining the role and historical meaning of the dissident movement.

Liubov Murzhenko: When Alik was arrested for the second time, I moved from Lozovaya to Kiev. I was lonely and scared. Once I went to Babiy Yar (the day before I listened to “Voice of America” and learnt that there would be a rally). Immediately in the crowd I spotted common citizens, KGB people and active youth. I approached the latter. Having explained who I was I said that I wanted to meet like-minded people. They advised me to leave my telephone number and promised that shortly someone’d pay me a visit. It was true. Soon a young man came. It was Sasha Feldman. He took care of our daily needs, helped us to get packages from abroad.

Before “the Leningrad affair” Mendelevich has written “The appeal to the people of the good will” in which he has said that they fully understood the risk they ran to and in the case of failure they asked for any help to their families. Since the affair attracted international attention afterwards, people from everywhere supported us, sent parcels. Though for these parcels the KGB made me write reports (I refused to do it) and labels me as a foreign secret service agent.

I.G.: How did the imprisonment of your husband affect your daily life?

L.M.: Once someone got arrested and my phone number was found in his telephone book. At that time I had an 6 month-old baby. I was called in for interrogation but I refused. First of all, I didn’t know the detainee. Secondly, I had a baby. In such cases an investigator comes to see a witness at their home. My Mom had just gone to work. I was breastfeeding the baby, still in my nightgown, with hair curlers on my head. A couple minutes after my Mom had left, without knocking on the door a district militia officer and two men in civil clothes came in. They asked if I’d go with them to the KGB. I refused again. Then they grabbed me by the arms and legs and pulled to the car. In only a night gown. In foul November weather. They pushed me into the car and my night gown remained in their hands. They threw it to me and locked me in. a couple of minutes later they brought my shoes and a rain coat (although a warm coat hung by the door) and my baby wrapped in some clothes from our apartment. Dressed like that – in a night gown, rain coat, shoes on bare feet, with hair curlers on the head and with a sloppily wrapped baby – I was brought to the KGB. They left me in an empty room with a barred window a single chair. I waited for about 2 hours. Then they took us to another room to see the investigator… After a useless interrogation they gave me 5 kopecks to get home. As the tram ride cost 3 kopecks, I would have owed them 2 kopecks. The way I looked, it was out of the question for me to take a tram. I took a taxi and told the driver would pay when we reached home. He didn’t say anything. Everything was clear – he picked us up by the KGB headquarters.

(The full text of the interview is available upon request)

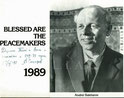

Alexey Murzhenko

(1942-1999)

1942, 23 November. — Born in Lozovaya, Kharkov region.

1952-1960 — Studied at Kiev Suvorov military college. Left it before completing studies without taking the oath.

1960-1961 – Attended the evening school for the working youth in Lozovaya and at the same time worked in construction, building the Kharkov – Kiev road. Graduated from the school with distinction.

1961–1962. — Entered the Moscow Finance institute. Worked as an inspector in Moscow. Along with V.Balashov, created and participated in the student underground group “The Union of Intellectual Freedom”. Wrote and distributed manifesto “The Union of Intellectual Freedom”.

1962, March — Arrested along with two former comrades from the Kiev Suvorov military college – Victor Balashov and Sergey Kuzmin as well as Yuriy Fedorov.

1962, 20 July. — Sentenced to: Balashov – 7 years, Murzhenko – 6 years, Fedorov – 5 years, Kuzmin – 4 years of deprivation of freedom in strict regime units (Art.70-1 and 72)

1962, September. — Transit to Sverdlovsk. Arrived in Potma. Transit prison of Mordovian camp administration “Dubravlag”. Held at camp 7 in Sosnovka station. Met representatives of other student underground groups. Became friends with Edward Kuznetsov.

1964–1967. — Tried for “camp rules violation”. Incarcerated in Vladimir prison. Punishment cells.

1967–1968. — Returned to camp 11 of “Dubravlag”. Met Daniel Sinyavsky and members of Ukrainian, Baltic, Armenian national groups. Released.

1970–1984. — Participated in an attempted hijack in Leningrad. Sentenced to 14 years of strict regime. Time served in Mordovian camps and a special regime camp 36 in Kuchino, Perm region. In 1971 met V.Balashov in the camp.

1984, 15 June. — Released.

1985. — Publication in London of letters from the camp.

1985, 4 June. — Arrested. Charged for violation of the supervision regime. Sentenced to 2 years in a special regime prison in Izyaslav, Khmelnitsky region.

1987, 4 June. — Released.

1988, 29 February. – Immigrated to the USA.

1999, 31 December. — Died in New York.

THE LENINGRAD HIJACK AFFAIR

(Excerpts from the book PRISON DIARIES by Edward Kuznetsov)

Their offence was to plan to fly a plane over the Soviet border to Scandinavia, though they never came near the aircraft. The plan was the last gesture of despair after losing all hope of being legally able to leave the Soviet Union for Israel. Their quixotic plan, which they knew was doomed to failure, did, in its effect on world opinion, help others to emigrate.

(From the introduction by Leonard Schapiro)

Between the 15th and the 24th December 1970, in the City Court of Leningrad, the following were charged under the Articles of the criminal Code of the RSFSR below: M.Y.Dymshitz, E.S Kuznetsov, S.I. Zalmanson, J.M. Mendelevich, I.I. Zalmanson, Y.P. Fedorov, A.G. Murzhenko, A.A. Altman, L.G. Khnokh, B.S. Penson and M.A. Bodnya.

Art.64a: “Treason, i.e. an act knowingly committed by a citizen of the USSR, prejudicial to the security, territorial inviolability and military might of the USSR…”

Art.15: “Responsibility of the preparation of a crime and for attempting to commit a crime.”

Art.70: “Anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda for the purpose of subverting or weakening the Soviet regime or for committing separate especially dangerous crimes against the State…”

Art.93: “Misappropriation of state or public property of especially large dimensions.”

According o the bill of indictment the defendants’ intention had been to use AN-2 12-seater passenger aircraft to take off along the Leningrad – Priozersk route and fly to Sweden. M.Y. Dymshitz, S.I. Zalmanson, I.I. Zalmanson, B.S. Penson and M.A. Bodnya pleaded guilty. M. Mendelevich, E.S. Kuznetsov, A.A. Altman, A.G. Murzhenko and L.G. Khnokh pleaded guilty in part only. Asked “Do you plead guilty?” Y.P.Fedorov replied, “Not under these articles.”

Of the eleven defendants, nine (excluding Murzhenko and Fedorov) testified that the single aim of their planned seizure of the aircraft had been to reach Israel. S.I. Zalmanson, her husband E.S. Kuznetsov, I.M. Vendelevich, A.A. Altman, B.S. Penson and M.A. Bodnya had, on more than one occasion, attempted to leave for Israel by official means, but either they had met with refusal at the OVIR 1 office or they had not been given the necessary employment reference, without with the OVIR would not accept their application.

1 Soviet government agency responsible for exit procedures.

Cross-examination of Alexei Murzhenko

I do not agree with the charges: 1) that I acted in accordance with any anti-Soviet views – my reasons were purely personal; 2) that I was involved in the preparation of the action – I did no such thing; 3) that I intended to steal the aircraft – I was sure it would be returned.

Murzhenko’s wife Liuba.

Has a one-year-old daughter. Didn’t know of the flight. Had received letter of farewell from Moscow after 15th June.

Defendants’ Final Pleas

Before I speak of my own case, I beg the court to show mercy towards Kuznetsov and Dymshitz.

I am in complete agreement with my lawyer. The procurator has asserted that I am anti-Soviet and that it was for this reason that I participated in this action. But this is not true. My first conviction totally unsettled my life. The fact that I took part in this undertaking is the consequence of my inexperience of life. My life has been up to now – eight years in Suvorov Military College, six years in camps for political prisoners, and only two years of freedom. Living my life in the backwoods I have never had the opportunity of applying my knowledge and I have had to bury it. You are deciding my fate, my life. If, as the prosecution has demanded, I receive fourteen years’ imprisonment, then this means you consider me incorrigible and have decided to abandon me to my fate. I have never pursued criminal objectives. I beg the court to determine such a term of imprisonment as will allow me to hope for happiness, for the future both myself and my family.

On 25th December, 1970, the Leningrad City Court, Chairman Ermakov, sentenced:

Dymshitz, M.Y. to the supreme penalty, the death penalty with confiscation of property.

Kuznetsov E.S. to the supreme penalty, the death penalty with confiscation of property.

Fedorov, Y.P. to 15 years special regime, without confiscation of property, in the absence of such. To be recognized as an especially dangerous recidivist.

Murzhenko, A.G. to 14 years special regime, without confiscation of property, in the absence of such. To be recognized as an especially dangerous recidivist.

The announcement of these sentences was greeted with applause by the “public”, whereas from the relatives came cries of “Fascists, how dare you applaud the death penalty!” ”Good lads!” “Don’t give up!” “We’re with you!” “We’ll wait for you!”…

Public Protests after the Trial

December 27th: A letter, signed by V.N. Chalidze, A.S. Volpin, A.N. Tverdokhlebov, B.I. Tsukerman and L.G. Rigerman, was sent to N.V. Podgorny, Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet. In it they requested that the murder of Kuznetsov and Dymshytz should not be allowed; that all who wish to leave the Soviet Union should be allowed to do so…

December 28th: Academician Andrei Sakharov sent a letter to the President of the USA, R. Nixon, and to the Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR, N.V. Podgorny, in support of Angela Davis; and M.Y. Dymshitz and E.S Kuznetsov, sentenced in Leningrad.

Victor Balashov (1942 - 2016)

The history of our “cadet” case started in Moscow and led to an arrest. First, I was arrested – on the way home from work near the underground station “Biblioteka Lenina” (Lenin Library) – as was Alik Murzhenko. (A.Murzhenko described his arrest in his book “An image of a happy man, or Letters from a special regime camp” – I.G.). Our first confinements – or misadventures – took place in the inner jail of Lubianka (Moscow KGB HQ – I.G.). We – Alik, Yura Fedorov and I – spent a couple of weeks there in solitary cells. All of us were thoroughly interrogated.

In terms of psychological torture, the first night was especially tough. Before being put in a solitary cell, I was sent (others were supposedly too) to the bania (baths –I.G.). It was big, cold, with no hot water. And above all I had the impression that this was where executions took place. Later it became known that often executions were often held in banias. The feeling of being completely naked and vulnerable was a real test of character, a push to resistance and understanding what to do afterwards.

The Chekists (original name of the KGB officers) considered our case to be a nationwide affair. But later they concluded that it was limited to Moscow and probably some other cities. It was decided we would be interrogated and tried by the Moscow department of the KGB and were transferred to Lefortovo (jail in Moscow – I.G.).

Before the trial Yura Fedorov and I were sent to the Serbsky institute (psychiatric clinic in Moscow – I.G.) – another test of strength to one’s mental health. The clinic was headed by the famous professor Lunts. Dzerzhinsky’s daughter was the chef psychiatrist. I went on a hunger-strike because the prospect of being locked in a lunatic asylum instead of standing trial did not appeal. I was seriously afraid – if you had no relatives the chances of getting out of there were almost nil.

When it was clear that arrest was inevitable, we thought it might be at least useful – at last we would meet everyone we wanted to meet and people, who were hard to meet – protesters (later, dissidents). Back then, you could have met them in Mayakovsky square, but it was too exposed. It was risky to be seen there – sooner or later on would get arrested. Our principle was to stay underground. That is why we avoided open activities – until the presentation of our manifesto. This took place on February 23 which was the Soviet Army Day (1962 – I.G.). That was the day we distributed all our leaflets officially. Before that we sent them by post but on that day they were distributed openly all around Moscow.

What was the concept of the manifesto and of the case itself? Neomarxism, or revisionism, was our philosophical position, not neobolshevism, of course. Our aim was not seizing power by force.

We hoped the manifesto could create a commotion: there was a certain – overt or covert – opposition, underground movement “Union of mind freedom” that appealed to the intellectual freedom of academic, religious, professional, and military institutions.

It was a kind of test: would it be possible to encourage students to unite as an intellectual mass to protest actions? But after the publication and distribution of the manifesto – after assessing the reaction – we decided to hold on. It was not the right moment yet. We had to go back underground, keep a low profile, and wait for the moment when it would become clear that “spring” had come. This was 2 or 3 weeks before our arrests.

The circumstances of publication of the manifesto were quite interesting. It was published at the closed publishing house of the Bureau of foreign military literature that was beyond KGB control - it belonged to the GRU, the State Intelligence bureau. (Victor Balashov worked there back then. – I.G.) First I made one photo copy and then multiplied them. The Bureau staff asked me: “Are you making pornography?” – “Yes, of course”.

When we were about to start our action, Alik and I had a very simple concept – the fewer the better. This meant that the two of us had to do everything, take all responsibility but create the illusion that there was an organization trying to change the Soviet world. An organization – it was crucial. We counted on an open trial and hoped to show the existence of a protest movement and to attract attention to this case. But most of all, we wanted to scare the regime – to make it something. And somehow we believed that people shared our views.

From a leaflet distributed by members of “The Union of Intellectual Freedom” on February 22, 1962

Compatriots, workers, brothers-students. Comrades!

The social order of our state hypocritically called democratic, for a long time was and

still is a reactionary, totalitarian regime. The dictatorship of the proletariat was replaced by the political dictatorship of the governing party which replaced the principal of loyalty to

Marxism with uncritical dogmatism. The constitution of the USSR contradicts the laws of public life; the state policy tramples on people’s essential needs, neglects our interests, and

constrains our natural desires. The Supreme party governmental apparatus dominates the worker through the administrative party bureaucracy, enslaving our freedom and will.

... Degeneration of ideas of democracy and real revolutionary Marxist socialism in, destruction of freedom of thought and restriction of right to freely criticize the government’s activity,

the cult of authoritative individuals, formation of political inertia in social movement, the corruption of social consciousness have led to the crisis of modern Marxist ideology as well as

the ideology of peaceful co-existence between states.

.. The rhetorical declaration of building of communism in the country – the sacrifice of the Soviet people for the sake of future generations - is logically untenable and not justified in

historical terms.

... We, "the Union of Intellectual Freedom", proclaim a revolutionary act to struggle for the revival of the original democratic party of the working people to bring social progress for the

Fatherland.

We struggle for the government’s observance in practice the pacific policy of coexistence... We demand real guarantees of constitutional freedoms, the authentic right of free political

existence, and the revival of the critically sustentative ideas instead of obligatory standard thinking. We demand the liberation of the individual from moral, ethical, and ideological dogma.

We demand material security and a high living standard for workers; we reject any increase in resources for the strategic defense industry. We demand tax reduction for workers, increase a pay

and reject any attempt to intensity labour output. We demand the full and valid right to govern the state, the right to define and to discuss current policy of the country.

We intend to fight for the true democratization of the legislative and executive authorities, for the decentralization of the legislative and executive branches of government, for the abolition of the party cult, for the eradication of extremely reactionary methods of ideological coercion. We are fighting to overthrow the political hegemony of the CPSU.